Welcome to our new members’ blog. From time to time members will post news, reviews, essays, photos and more replacing our much loved newsletter. Access the newsletter archive here

March 2025 Blog no. 6

March’s blog is a brief paper based around the chambered cairn at Cladich, some unrecorded rock art and possibly more…

Prehistoric Cladich -a preliminary glance, by Simon Davies

Observations and meandering around the hamlet of Cladich, Loch Awe side, Argyll

February 2025 Blog no. 5

This month’s blog is by way of a downloadable report by the esteemed Neolithic specialist Dr Alison Sheridan of the excavations by Lionel Masters at Lochhill and Slewcairn.

December 2024 Blog no. 4

*The Botanic age, a review of a review, by Ewen smith

An interesting, and arguably long overdue, exploration of technological innovation pre-dating the Stone Age. The fundamental problem such a study has faced has been the perishable nature of plant material compared to the longevity of stone in the artefact record. However, this article suggests that while new technology will give us access to a fossil record which pre-dates the emergence of stone tools, some evidence of this type of investigation has already been found. A specific example (close to home) was discovered (2016) by Prof. Karen Hardy ** of the University of Glasgow, who with colleagues “found a tiny piece of non-edible wood in the fossilised tooth plaque of a 1.2 million-year-old hominin in Atapuerca, Spain”. Further examination of marks on the teeth suggested that the wood was a tooth-pick.

But suggestions from the 1970’s argue that “containers such as baskets were amongst humanity’s earliest possessions”. And how importantly might this have been in human evolution? Clearly, then as now, containers could be used for storage of materials, and for carriage. This latter would have been more significant for gatherers in the hunter/gatherer communities, and for carrying babies, mostly also associated with gatherers in H/G communities. Furthermore, and perhaps controversially “It is thought that this need stemmed from a uniquely human transition that started 6 million years ago … the move to walking on two legs”. In short, well before the Stone Age.

Thus far, therefore, we have a mixture of evidence (e.g. a toothpick, 1.2 m. years old and digging sticks, 375,000 years ago) and rational conjecture (containers and slings, drinking vessels) to support the notion of a Botanic Age going back potentially millions of years and conceivably facilitating bi-pedalism.

The irony age may lie in our recognition of the continued use of plant tools before, during and long after the pre-eminence of stone, while our studies continue to focus on tools made from stone. Definitely a thought provoking article, and an introduction to Prof. Hardy’s forthcoming lecture (see below).

* “The Botanic Age” by Sophie Berdugo:- New Scientist; 9 November 2024

** Prof. Hardy is giving a lecture at the University of Glasgow, on the evening of 4 December 2024 (17:30), Entitled “Paleo fact or flintstone fantasy? The Palaeolithic and its relevance to today’s world”.

Full details available at the following site:- https://www.gla.ac.uk/schools/humanities/research/archaeologyresearch/latestnews/headline_1126409_en.html

*With apologies that the posting of this post-dates the lecture referred to.

November 2024 Blog no. 3

An Archaeological tour of the isle of man, by Susan Hunter

The Isle of Man situated at the crossroads between Ireland, northwest England, Wales and the southwest side of Scotland saw many invaders over the years, some from the neighbouring countries while others came from places like Scandinavia. The ownership of the island over the years has also changed. All of this is reflected in the archaeology of the Isle of Man which is rich in the influences of various cultures, religious traditions and nationalities. The flora and fauna although not dissimilar to its neighbours’ has no foxes or deer. There are also Manx cats and the Loaghtan sheep which are peculiar to the island. The hedgerows in the countryside are particularly wide, full of growth with shrubs grasses etc, ideal for small animals and birds. In some ways the Isle of Man is a miniature landscape of the British Isles but with its own additional features.

The archaeology also takes influences from its neighbours; court cairns from Ireland and Clyde cairns from Scotland. Some of these cairns are spectacular. King Orry’s Grave, a Neolithic chambered cairn on the north edge of the village of Laxey is now seen in two sections. The first is tucked in front of a residential building on the east of a road and the probable west end of the cairn sits on the other side of the road within a garden. In its day this cairn must have been enormous. What remains on the east side are the remains of a well-preserved horned cairn with forecourt and multiple linear chambers, while to the west is a double chamber with a single upright orthostatic stone. Was this one approximately 60m long cairn, or was there originally two cairns. Excavations were undertaken in 1953 by B.R.S. Megaw. Neolithic undecorated pottery was found similar to that found in Clyde tombs in Scotland and court cairns in Ireland. Flint tools and knapping debris was found at the site.

Another Neolithic Chambered Long Tomb Cashtal yn Ary (also known as King Orry’s Castle) is found in the Maughold Parish. First evidence at the site relates to burning that may have been a cremation platform. A second horned cairn with a forecourt and five massive linear chambers was built within a trapezoidal cairn. The cairn was enclosed within kerb stones and under one of the cairn’s horns an earlier stone cist and low mound were found. The cairn was later expanded to form a rectangular shape covering the initial cremation platform. The earliest excavation of the cairn took place in the 1880s with later work carried out in the 1930s by Fleure and Neely. Fragments of a shouldered bowl were recovered from the first chamber.

Another intriguing and unusual Neolithic chambered tomb is Meayll Circle which in not in the style of Scottish Clyde cairns or Irish court cairns. It is situated on the high ground above Port Erin with extensive views over much of the island. The only tomb that this structure reminded me of was Dowth in the Boyne Valley, although this similarity was only because of its outer design. This tomb is circular and has six external entrances each leading into double chambers where deposits were placed. Unlike Dowth only a single stone was present in the central area. It could have been a precursor to the later building of Dowth. It is one of the most intriguing tombs that I have come across. Excavations took place on different occasions in the 19th/20th century and many fragments of round-based bowls, cremated human remains, flint tools and some arrowheads were found in the chambers.

To reach the Meayll Circle you pass RAF Cregneish – a Chain Home Low (radar) station operating throughout WWII situated on top of the hill. Both of the above features can be seen clearly coming into land at the Ronaldsway Airport.

The Isle of Man does not have any stone circles which seems unusual for an island lying in the middle of the North Sea between England, Scotland and Ireland.

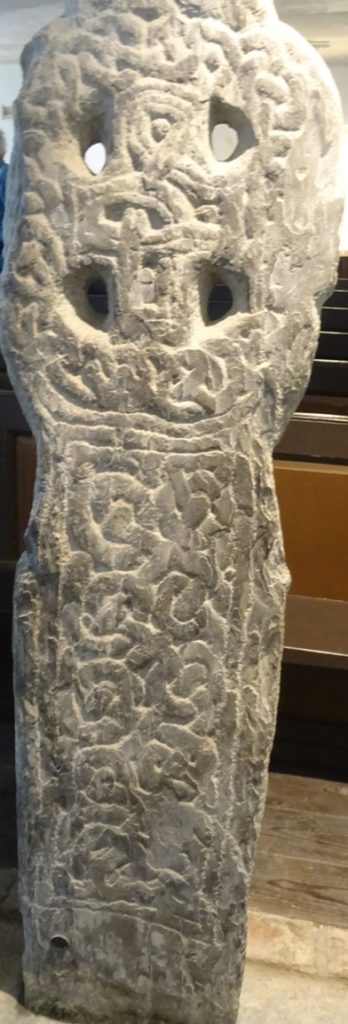

Isle of Man has considerable quantities of carved pre-Norse, Norse and medieval grave markers and crosses. A collection of 60 pieces has been brought together from the immediate churchyard area, keeill (an early chapel site) and other sites within the parish, at Kirk Maughold into a shelter designed by Armitage Rigby. The collection includes simple incised cross slabs, markers with Latin inscriptions, two grave markers with Angle-Saxon runes, stones showing connection to the Welsh kingdom of Gwynedd, the Pictish kingdom and Ireland as well as rich Norse period decorative slabs some with Norse runes and some with both Gaelic Ogham and Norse runes. Within the church is the Maughold cross. This is a market cross showing one of the earliest representations of the symbol of the Isle of Man and its rulers; Ny Tree Cassan/the Triskelion/the three legs of Man.

Some of the ancient parishes in the Isle of Man take their name from saints. Kirk Andreas is thought to be St Andrews Parish church. Kirk is the Norse word for church and at this church a fine collection of grave markers are seen including Christian pre-Norse grave markers. One was found with a bilingual inscription in Gaelic Ogham characters and Latin with parallels to stones found in Wales and Cornwall. Four crosses of particular interest are Gaut’s cross, the Siguard cross, Thorwald’s cross and Sandulf’s cross. These grave markers and crosses are protected and displayed within the church.

Kirk Michael has the graves of some of the Bishops of the Isle of Man. A silver hoard of coins from England, Ireland, Normandy and the Isle of Man, buried about AD1065, was found in the remains of a nearby earlier church. Within the church is a fine and large collection of Norse grave markers and crosses with extensive runic inscriptions, Christian and Norse iconography and motifs, some of which are identified with the name of the sculptor Gaut/Gautr. Elaborate interlace designs include the ‘Dragon’ cross.

Another old church that protects numerous well preserved pre-Norse and Norse grave markers that were in the graveyard is St Brendan’s Church. It dates to the 1770s but incorporates an earlier building. This building was again found on the site of an earlier keeill.

Peel Castle sits on St Patrick’s Isle on the west coast looking towards Ireland and the south-western coast of Scotland. Excavations in 1982-87 found Mesolithic artefacts and an Iron Age settlement. It is suggested that an Early Christian monastery was situated on the Island, along with the remains of one and possibly two keeills and a round tower in the Irish traditions. Defensive elements are seen around the castle’s seaward and landward sides.

The other castle on the Isle of Man is Castle Rushen which is a port area linked to England and Wales. This castle is connected from the 12th century with the building of fortifications by the Norse Kings of Mann and the Isles. It became the base for the Kings and Lords of Mann’s administration through the medieval and early modern period. The castle has a history of treaties and sieges.

Other interesting structures lie over a causeway to St Michael’s Isle, passing a 12/13th century chapel. At the north end of the track is the substantial stone-built Derby Round Fort possibly built around 1540 as part of Henrician coastal defence.

Chapel Hill Balladoole situated on top of a hill with fine views to the south is a multi-period site. Activity was found from the Mesolithic Period onwards including a Bronze Age cist, Iron Age Fort and houses, an early Christian cemetery, a Viking ship burial excavated in 1945 (another ship burial at Knock y Doonee was excavated in 1918) and Gaelic-Norse keeill Vael (St Michael’s Chapel) all bounded within a low stone wall. The ship burial contained a male skeleton accompanied by weaponry and horse gear much of which is on display in the Manx Museum. Th aerial view of the area below is courtesy of John Worham.

Aerial photo courtesy of John Worham

Cregneash village is a rural ‘living village’ where the older, rural traditions of the Island including fishing, farming and rural crafts can still be witnessed. Two-thirds of the buildings and much of the surrounding land is owned and managed by Manx National Heritage. The buildings are of interest to those who carry out building surveys on Scottish farm buildings. Of particular interest is how the thatch is tied on.

The Braaid is a fascinating site and the aerial photograph by John Worham gives a good overlook of the site. Three stone structures, two rectangular and one circular, are seen. The structures are dated to the Viking and Iron Age Period. There are no other similar so well-preserved structures standing to this height on the island. At one time it was thought that they were two stone avenues and a stone circle. Archaeological investigation in 1962 confirmed that the rectangular buildings were large Norse longhouses. The building to the right, 20m long x 9m wide, is typical of known Viking buildings in other areas with bowed walls representing a boat-shape. The side walls are massive being 2m thick and their bowed shape is designed to absorb the sideways thrust of the roof timbers and to bolster the insubstantial gable walls built either of turf or timber. The second rectangular building to the left is thought to be a cattle byre with stone walling along the north wall. The measurement of this building was still substantial at 18m x 8m externally but appears to have had a low lightweight roof not requiring the curved walls. The buildings were found to have been reused in the late-Medieval/post-Medieval Period.

When the circular structure was excavated in 1930 it confirmed that the feature was a large Iron Age domestic roundhouse although it did not completely rule out an earlier Neolithic or Bronze Age stone circle. At 16.5m in diameter it is not as large as the timber roundhouse built at Ballakeigan Farm or the circular earthwork known as Manannan’s Chair. The Braaid round house relies for its structural strength on massive standing stones placed around its circumference, between which walling faced with stone and filled with an earth core was built up. It is presumed that the roof would have been a low turf structure supported on a network of timber posts, rafters and brushwood.

Around the site two tall stones standing on their own and other stones at the ends of structures made us wonder if the site indeed start off as a stone circle or a circle and two stone avenues later adapted by later generations into a habitation site. It certainly was one of the most exciting sites we visited on the Isle of Man.

Aerial photo courtesy of John Worham

Turning to industrial archaeology on the Isle of Man, mining in the Isle of Man is known from prehistoric evidence and literary medieval sources with mining continuing into modern times. By the late 18th /19th century it grew to an industrial scale and the veins of ore found at Laxey became the most prolific. Galena, silver and copper ores were mined but the most important was zinc blende which meant that the Great Laxey Mine grew and developed supplying half of the British Isles production in the late 19th century. The best-known feature of the mining complex is the Lady Isabella Wheel which first turned in 1854 and is now the largest turning waterwheel in the world. The Lady Isabella kept emptying water out of the mines until the late 1920s. It is now run by the Manx National Heritage. There are many interesting industrial features connected with the working of the mine that have been preserved in and around the waterwheel, some within the surrounding woodland. You could probably explore this area for many hours and possibly all day, there is so much to see.

The Royal Chapel of St John and Tynwald Hill was and is the focus for the midsummer open-air assembly where judgements are given, and business transacted in ways seen throughout the Norse world at Thing or Ting sites. The etymological origin of ‘Tynwald’ is the same as that for Dingwall in Scotland, Tingwall in Orkney and Shetland, Pingvellir in Iceland etc, being the Old Norse for ‘assembly field’. Around the 5th July the Man Tynwald Court meets in the open air using a ceremony first written down in the 15th century but based on older traditions which owe their origins to the Norse rule of the Isle of Man and possibly pre-Norse ‘Celtic’ assemblies.

A visit to the Isle of Man would not be complete without a visit to the Manx Museum in Douglas. Wonderful displays from the Mesolithic onwards are well presented and described including displays of Viking hack silver hoards found on the island.

Apart from the archaeology and history of the island there are other holiday adventures, steam trains, one going up to Snaefell (snow mountain) and of course the horse drawn tram along the front at Douglas. The bus transport systems on the island are also really good.

The above information is based on Archaeology of the Isle of Man Field Notes written for the travel company Andante by Dr Andrew Foxon. Andrew is a graduate of Glasgow University and a member of Glasgow Archaeological Society. He was a wonderful, very knowledgeable guide and companion during our trip to the island. The above is only a glimpse of the fantastic archaeology and history of the Isle of Man. The island would make a great ‘Jolly’ destination for ACFA members.

October 2024 Blog no. 2

Loch Tay Crannog Reconstruction, by Ewen Smith

The devastating fire in 2021 that put an end to the replica crannog constructed in Loch Tay, near Kenmore, set in train a complete re-thinking of how this important archaeological site should be replicated. There never seems to have been an “if” involved, correctly in my view, and the new site opened in April this year.

I recently had the pleasure of visiting the site and saw firsthand the progress towards realising their Vision*,”to become a National Treasure” impacting on and benefitting the disparate communities the site serves. In addition to a small display of artefacts discovered from the new site (and from earlier crannog archaeological investigations), there is a real size Iron Age village where houses demonstrate cooking methods, textile and dye making, wood and metal working. If I were to pick out only one building so far, it would be the magnificent round house, displaying the considerable knowledge and skills that the original community of builders shared.

The construction of the village, and the demonstrations of these various tasks are all undertaken using contemporary resources and methods. In that sense, the educational aspirations of the designers are already being met, far beyond the ability of the original replica site. (Missing, however, are teaching methods for fire lighting using only dry sticks … the highlight of our daughters’ visit some 30 years ago!)

Also missing is a crannog! However, work on the first of three crannogs began on 26 August 2024. Like all the other resources used to create the village so far, locally sourced materials will be used whenever and wherever possible, and reed beds along the River Tay will doubtless prove invaluable for the building of roofs, and other purposes. In addition, there are significant collaborations with disparate communities, from refugee integration to mental health. Various apprenticeships have been utilised, and a diverse workforce recruited on at least the Real Living Wage, and avoiding inappropriate Zero Hours Contracts.

It is an undeniably impressive venture, and has come at a cost (approximately £5,000,000** so far) with on-going donations being sought, in addition to the entry charges (£12:50 Concession). It would most certainly have cost a great deal more, were it not for the fantastic support of the teams of volunteers!

Thanks to the Scottish Crannog Centre for the use of their photographs

** Support has come from many organisations, ranging from, perhaps predictably, Perth & Kinross Council to (less predictably?) the EU.

September 2024 Our first member’s blog

Thanks to Janet MacDonald for our inaugural blog post.

Around the Lake

I recently spent a few days in the Lake District, and though I’d share a few highlights of the visit with ACFA members.

Bowness-on-Windermere is home to the Windermere Jetty Museum, originally built to house the collection of boats made by local businessman George Pattinson, and is now run by the Lakeland Arts Trust. The museum opened in 1977 and has a variety of steam launches and other boats on display, including the catamaran Trimite, which broke the world water speed record in 1982, reaching a speed of 144.16mph.

The Trust aims to conserve and/or restore the boats in its care, in some cases making the decision to conserve the fabric, in others to return the vessel to operational use, but in each case determining its significance in order to guide any decisions.

A nice example of a restored vessel is the steam launch ‘Branksome’ (1896), which can be seen inside the museum, while outside is the hull of the twin-screw steam yacht ‘Esperance’, built in 1869 by T.B. Seath of Rutherglen, and which was the inspiration for Captain Flint’s houseboat in Swallows and Amazons. In the boathouse can be seen the ‘Swallow’ and the ‘Amazon’ as used in the 2016 film version of Arthur Ransome’s famous book.

Another boat built in Rutherglen was the steam yacht ‘Britannia’, owned by Col. John Ridehalgh. It was 107 feet long, and could carry up to 122 passengers. The model (below) was also made by Seaths.

Several boats were salvaged from underwater, including the ‘Esperance’, the hydroplane ‘White Lady II’ which sank in Windermere during a race in 1937, and the steam launch ‘Dolly’, raised from Ullswater in 1962, having sunk in 1895.Beatrix Potter’s flat-bottomed rowing boat sank in Moss Eccles tarn in 1950, and was brought up after 26 years at the bottom of the tarn.

Also in the care of the Lakeland Arts Trust is Blackwell House, a beautiful Arts & Crafts House near Bowness. Designed in 1898 by M.H. Baillie Scott as a holiday home for wealthy Manchester industrialist Sir Edward Holt and his family, it was later used as a girls’ school from WW2 until 1976, and has been faithfully restored to its former glory. It contains beautiful tiled fireplaces by William de Morgan, carved oak panelling (some of which was reclaimed from a church in Warwick), delicate stained glass, and a beautiful peacock-patterned wallpaper frieze in the Main Hall. Baillie Scott himself designed a block-printed and stencilled hessian wall covering, which has been conserved and restored to the dining room.

At the northern end of Lake Windermere is Ambleside, near which you can go gallivanting around Galava Roman fort, originally constructed in wood around the late 90s AD. This was replaced by a bigger stone-built fort (internally 395×270 feet) between AD122 and AD 125, and could have housed a garrison of around 500 men. A project currently underway by Edinburgh University and the Trimontium Trust is looking at a particular period of conflict in the fort’s history – keep an eye out for more on this.

In Ambleside itself is the Armitt Library, Museum and Gallery, founded by Mary Louisa Armitt. As well as an extensive collection of books on local topics, it currently has an exhibition on the history of fell-running in the Lake District, a number of paintings by German artist Kurt Schwitter, who painted portraits of local people and hotel visitors during WW2, and a history of Beatrix Potter, looking not only at her career as an author and artist, but also as a famer, sheep breeder, estate manager and conservationist – on her death she bequeathed 1600 hectares of land and 14 farms to the National Trust. On display are some of her paintings of fungi, a particular interest of hers, and the Armitt holds several hundred of her natural history illustrations. Other items of interest include a 17th-century carved oak press, the largest on record. There are also artefacts from the Roman period and later, and accounts of some of the area’s most distinguished residents.

Finally, for those of a nautical bent, I’d highly recommend a cruise of the lake, complete with commentary, on one of the many vessels that sail up and down its length, from the most modern of the fleet, the ‘Swift’, launched in 2020, the ‘Swan’ and the ‘Teal’ from the 1930s, or the ‘Tern’ which has been carrying passengers on Windermere since 1891, or if you’re feeling fit, hire one of the traditional rowing boats and get rowing!

August 2024

To introduce the blog here’s a photo of a survey team hard at work, unusually enjoying some sunny conditions, in the Halterburn Valley in the Scottish Borders.